HIGH-DENSITY URBAN AREAS AND VERTICAL GROWTH

This project begins with a series of investigations into Hong Kong's Kowloon Walled City, a globally renowned example of extreme urban density and informal urbanization. As a highly compact and anarchically developed urban space, the Walled City offers critical insights into spatial utilization and social interaction under extreme conditions. Its complex vertical structures, mixed-use layouts, and extraordinarily dense population serve as a foundation for examining the dynamics of urban environments in contexts of rapid growth and limited regulation.

Through a comprehensive study of the Walled City’s history, spatial organization, and socio-ecological systems, the project seeks to decode the underlying logic and driving forces behind this unique urban form. Kowloon Walled City emerged not only as a response to land scarcity and the pressures of rapid urbanization but also as a self-organized system created in the absence of formal legal and institutional frameworks. Its architectural typologies are characterized by vertical layering, shared spaces, and mixed functionalities—qualities often overlooked in conventional urban planning.

Building on these insights, the project explores how the informal practices of the Walled City can inform contemporary design strategies. The aim is to reinterpret its complex spatial layering, efficient resource use, and community-driven principles into solutions for modern urban challenges. Design proposals focus not only on optimizing functionality within high-density environments but also on fostering community cohesion and spatial diversity through innovative approaches. For instance, reimagining modern high-density housing inspired by the Walled City might involve the integration of flexible spatial modules, open areas for community interaction, and vertically integrated public spaces.

Building upon the spatial and cultural elements derived from the Kowloon Walled City, the project initiates a series of exploratory designs in the context of Oakland, California. As a diverse urban center facing the dual challenges of population growth and limited land resources, Oakland provides a compelling site for experimenting with the integration of Kowloon's design principles into contemporary urban needs.

Drawing inspiration from Kowloon’s strategies for high-density spatial organization, the project seeks to incorporate its core characteristics—vertical layering, mixed-use functionality, and community-driven autonomy—into Oakland's urban landscape. The design leverages modern construction technologies and materials to achieve more efficient integration of multifunctional spaces while maintaining the essential qualities of shared spaces and community interaction. For instance, modular architectural units are introduced to enable flexible spatial configurations that adapt to varying demographic and community needs. Vertical greenery and communal terraces are incorporated to provide ecological spaces and collective activity areas, while multi-level transportation and service nodes are strategically positioned to ensure mobility and accessibility within a dense urban fabric.

In the Oakland prototype, the focus is placed on balancing functional density with human-centered experiences. The project not only seeks to optimize land use but also aims to create a composite community that accommodates diverse cultures, economic activities, and lifestyles. Public spaces are positioned as a central feature, with private and public domains intricately interwoven both vertically and horizontally, forming a network of interconnected yet distinct spaces.

Through these explorations, the project aspires to offer a replicable model for addressing the challenges of high-density urbanization on a global scale. It aims to tackle issues such as housing shortages and spatial constraints while promoting more inclusive and sustainable urban development. At the same time, this effort serves as a tribute to the legacy of the Kowloon Walled City, transforming its unique spatial ingenuity into a forward-looking design language tailored to contemporary urban contexts.

_2022

Kowloon Walled City was a historically complex and symbolically significant urban settlement. Its formation, development, and eventual demolition reflect the historical and social transformations of Hong Kong.

Initially constructed as a military outpost by the Qing government in the 19th century, the Walled City was intended to strengthen control over the Kowloon Peninsula. However, after the signing of the Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory in 1898, most of Kowloon was leased to Britain, while the Walled City remained under Qing sovereignty. This unique status created a legal grey area that set the foundation for its informal development.

Following World War II, the population of the Walled City expanded rapidly as refugees moved in. By the 1980s, the Walled City had become one of the most densely populated urban areas globally, housing over 30,000 residents within an area of just 2.7 hectares. Its compact vertical structures and high population density made it a unique urban phenomenon.

The Walled City was often criticized for its governance and sanitation issues, resulting from its unregulated growth. The absence of formal authority led to safety and hygiene problems and fostered activities such as unlicensed clinics, drug trade, and illegal businesses, although these services were essential for the community.

In 1987, amid the backdrop of Hong Kong's impending handover to China, the British and Chinese governments reached an agreement to demolish the Walled City. Demolition began in 1993 and was completed in 1994. The site was subsequently transformed into Kowloon Walled City Park, preserving parts of its historical heritage as a tribute to this unique community.

The infrastructure of Kowloon Walled City was characterized by its informality and improvisation:

Buildings and Spatial Organization

Structures were constructed incrementally by residents, creating a dense vertical layering of buildings. Most buildings ranged from 10 to 14 stories, but the lack of unified planning led to narrow passageways and poor lighting and ventilation.

The interconnected corridors and staircases between buildings formed a labyrinth-like network, allowing residents to move seamlessly across different levels.

Water and Electricity Supply

Water and electricity were often obtained through illegal connections to the city’s main supply. Despite the risks, these systems supported the community's basic needs and were managed informally by residents.

Sanitation

Sanitary conditions were poor, with limited garbage disposal and drainage systems. Public toilets and makeshift sewage systems were common, leading to an overall degraded living environment.

The “fragmented spaces” of Kowloon Walled City—resulting from its spontaneous and non-linear spatial organization—fostered a high degree of cultural and activity diversity:

Multifunctionality and Mixed-Use

Buildings often combined residential, commercial, and industrial functions. For example, a single structure might house family residences, unlicensed clinics, artisan workshops, and food processing facilities. This multifunctionality significantly increased land-use efficiency.

Community Self-Organization

In the absence of external governance, residents developed self-organized networks to meet their needs. The Walled City contained schools, clinics, food stalls, and small businesses, creating a self-sustaining community ecosystem.

Cultural Diversity

The residents, coming from various regions and backgrounds, formed a culturally diverse community. Small businesses and workshops created vibrant social interactions and connections among residents.

Creativity and Adaptability

Faced with limited resources, residents displayed remarkable creativity. Spaces were cleverly divided and utilized, resulting in a unique "urban collage" of tightly integrated functions and spaces.

same difference

Kowloon Walled City in Hong Kong and West Oakland in California, though situated in vastly different cultural and geographic contexts, provide compelling case studies in urban density, mixed-use development, and community-driven adaptations. Both serve as examples of how residents can creatively respond to challenges posed by limited resources, neglect, or insufficient governance, while also showcasing unique contrasts in their legal, spatial, and developmental trajectories.

Both Kowloon Walled City and West Oakland demonstrate high-density land use and a multifunctional approach to space. The Walled City, with its vertical, layered architecture, combined residential, commercial, and industrial functions in a dense, compact area. Similarly, West Oakland’s history as a hub for industrial and residential uses reflects a pragmatic blending of functionality, albeit on a more horizontal scale.

Community-driven autonomy is another shared characteristic. In the Walled City, residents established informal systems for water, electricity, and social services in the absence of formal governance. Likewise, West Oakland communities have organized grassroots efforts to address systemic neglect and environmental justice, showcasing resilience and collective action.

Cultural diversity further unites the two. Kowloon Walled City’s population was composed of individuals from diverse regions and backgrounds, fostering a unique social fabric. Similarly, West Oakland, as a historic center for African American culture and immigrant populations, has long been a site of cultural richness and artistic innovation.

Despite these parallels, significant differences emerge. Kowloon Walled City existed in a legal vacuum, allowing it to develop without external regulation, but at the cost of poor sanitation and infrastructure. In contrast, West Oakland operates within the framework of U.S. urban planning policies, experiencing both systemic neglect and structured redevelopment efforts.

Architecturally, Kowloon Walled City was characterized by vertical, labyrinthine spaces, while West Oakland is defined by low-rise residential buildings and industrial warehouses. The infrastructure in Kowloon was largely improvised and illegal, whereas West Oakland, despite periods of decline, has benefitted from gradual improvements through public and private investments.

The economic base of the two areas also differs. Kowloon relied on small-scale, informal economies, whereas West Oakland historically thrived on industrial activity and is now transitioning towards mixed-use developments driven by technology, art, and culture.

The redevelopment pathways also contrast sharply. Kowloon Walled City was entirely demolished in 1994, replaced by a park that preserves its historical memory. West Oakland, however, has undergone incremental redevelopment, balancing the preservation of its cultural identity with modernization. This includes mixed-use projects aimed at fostering inclusivity and sustainability.

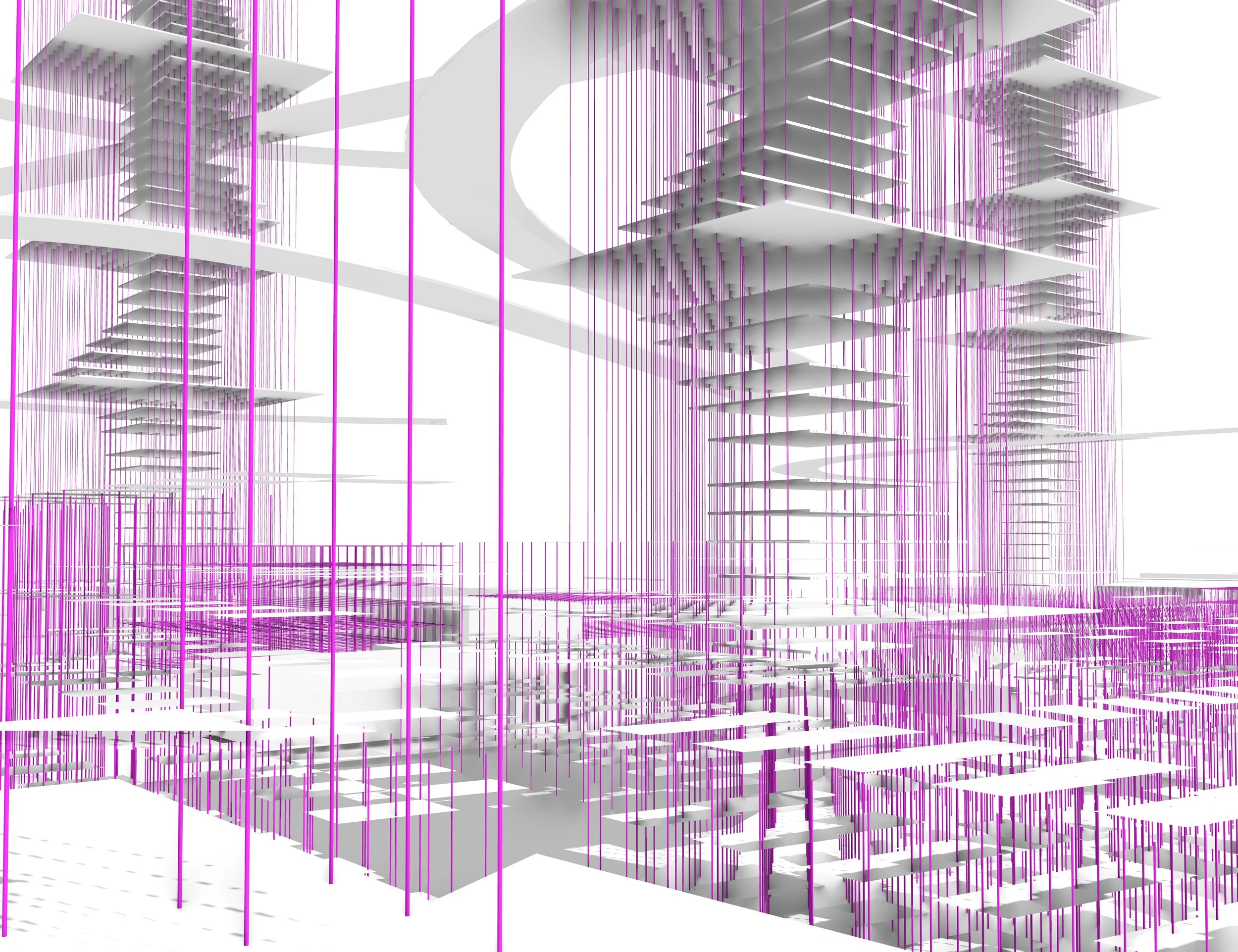

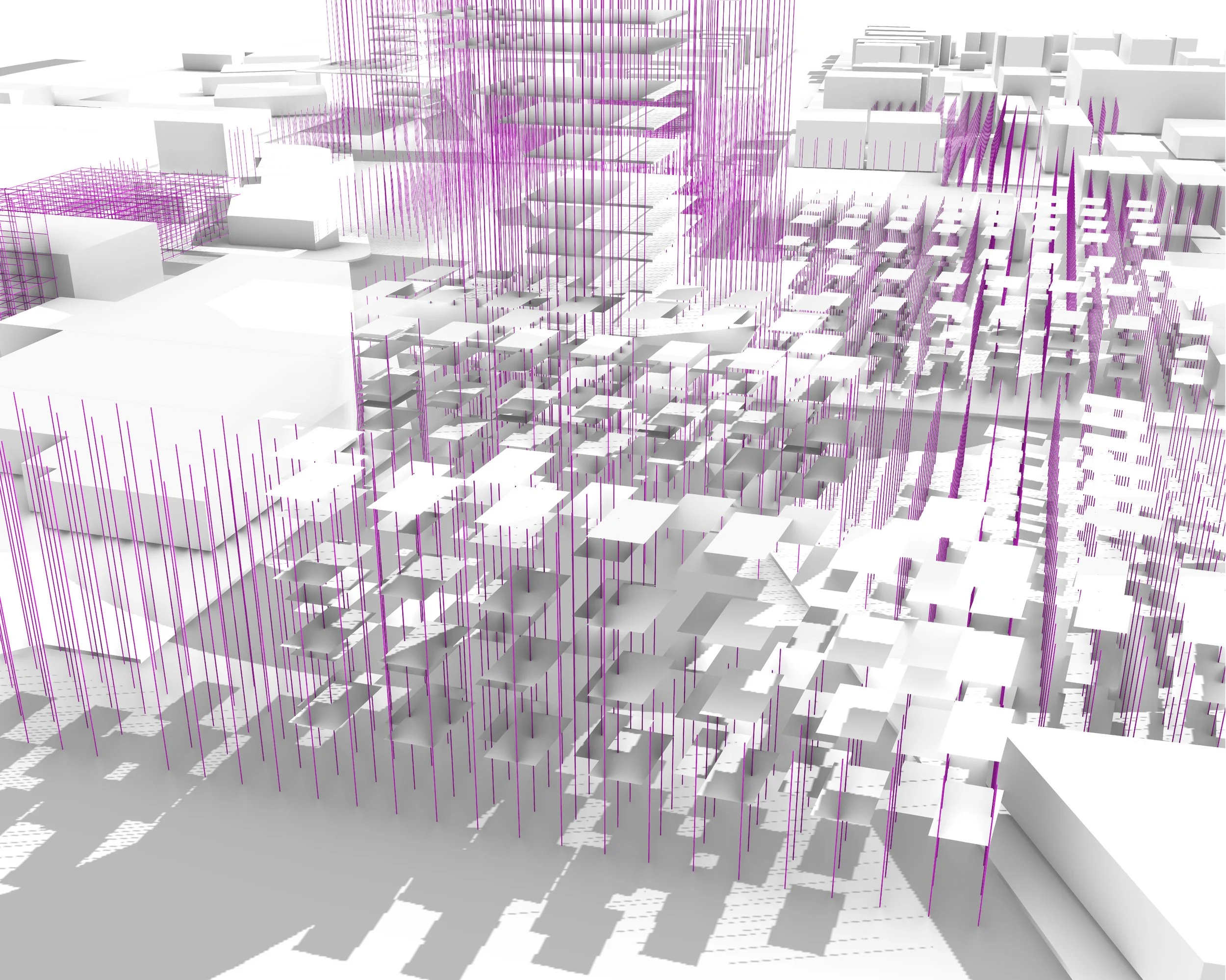

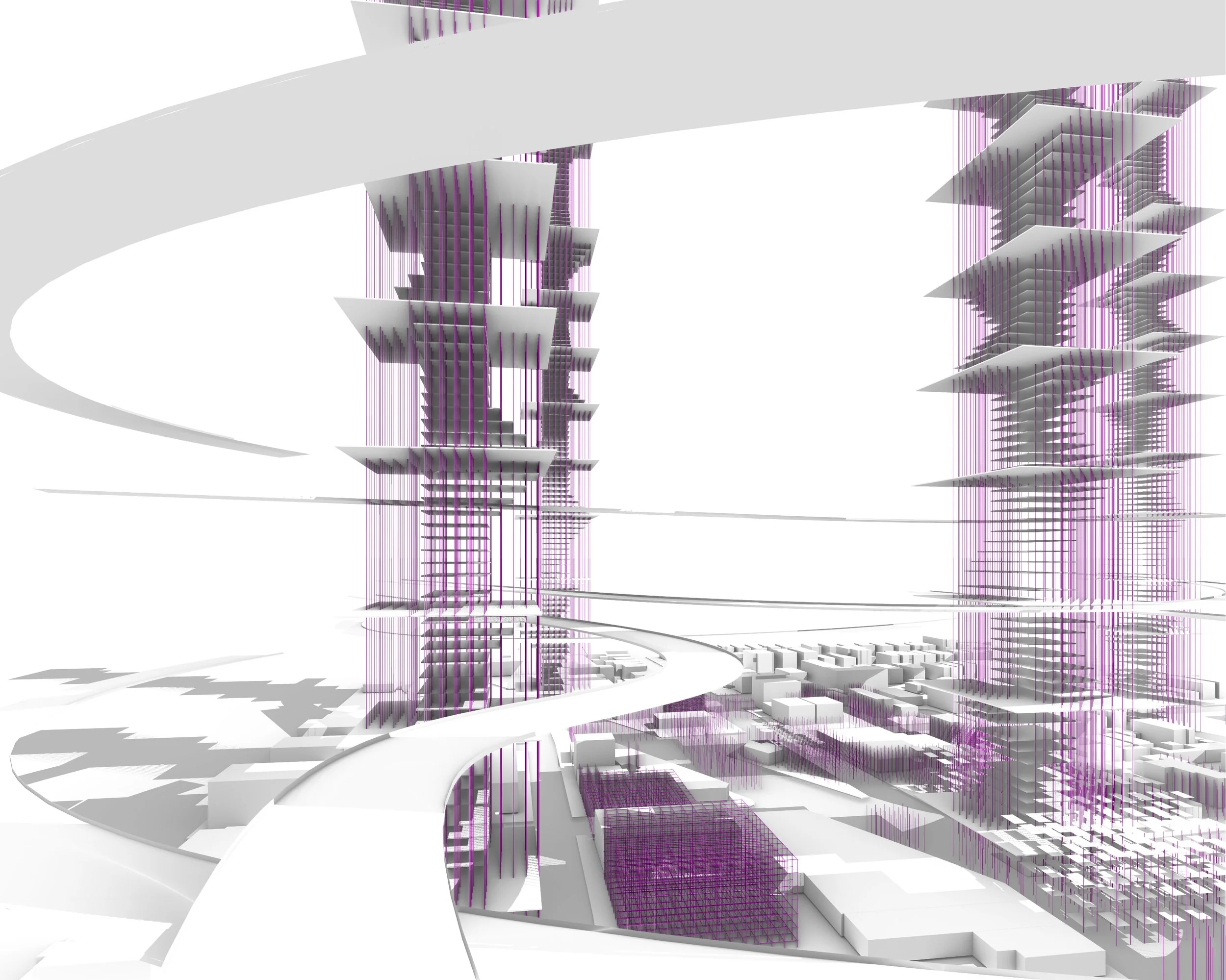

Designing Vertical Urban Growth in West Oakland: A Modular Framework for Community-Driven Development

The proposed design concept centers on West Oakland's main street as the foundation for a transformative urban growth model. By deploying fundamental structural elements such as "columns" and "slabs" across the area, this framework establishes a modular and flexible base for future development. These structural components are not merely physical elements but serve as the conceptual and operational core of the design, enabling a balance between foundational infrastructure and organic spatial growth. The goal is to empower communities to independently construct functional spaces that adapt to their evolving needs while fostering a cohesive urban identity.

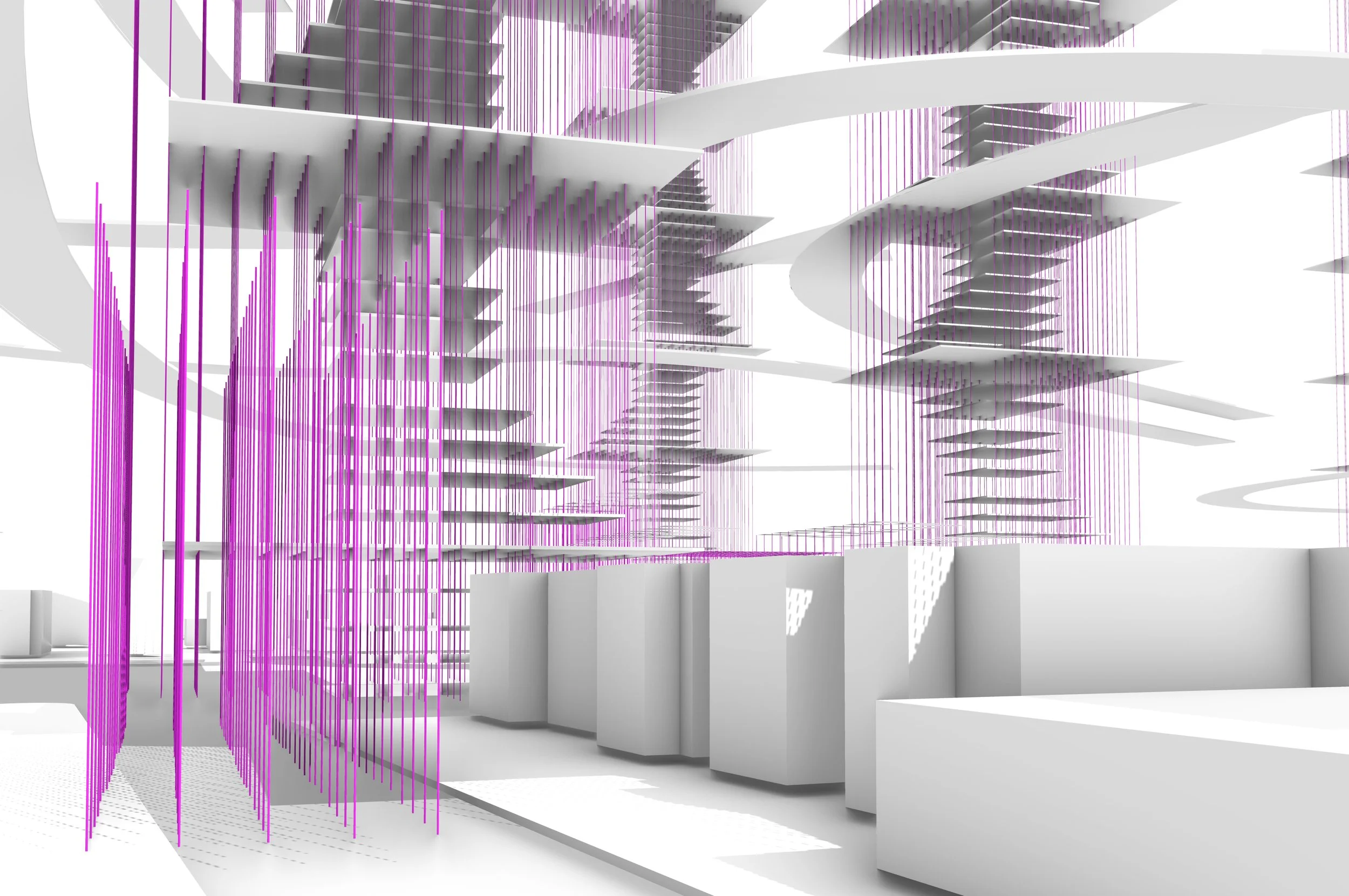

This approach prioritizes vertical urban development to address the challenges of limited land resources and to counteract the horizontal sprawl that often characterizes urban expansion. Key transportation nodes, particularly intersections, are identified as pivotal growth points. These intersections are reimagined as vertical hubs for multifunctional spaces, including high-density housing, co-working environments, and public amenities, contributing to the creation of dynamic and layered urban nodes. By building upward, the design harnesses spatial efficiency and reduces the strain on ground-level infrastructure.

An integral aspect of the design is the introduction of elevated pathways, which serve as both transportation corridors and public spaces. These elevated connections alleviate ground-level traffic congestion and provide a safer, pedestrian-oriented circulation system. In addition, they incorporate elements such as green corridors and recreational spaces, enhancing the ecological and social quality of the urban fabric. By linking various buildings and zones, these high-altitude pathways foster connectivity and enable a multidimensional urban experience.

The framework’s open-ended design philosophy emphasizes adaptability and inclusivity. Once the foundational structures are established, individuals, communities, and organizations are encouraged to co-create spaces that reflect their specific cultural and functional needs. This participatory approach empowers residents, fostering a sense of ownership and community cohesion while ensuring that the city evolves in a manner that aligns with its diverse social and cultural fabric.

Functionally, the design integrates multiple layers of public and private spaces to support diverse activities. Ground-level spaces accommodate commercial and social functions, while mid-levels house residential and office uses. Upper levels include shared terraces, vertical farms, and recreational areas, creating a harmonious balance between functionality and leisure. By encouraging vertical integration and spatial diversity, the design fosters a vibrant, sustainable, and inclusive urban environment.

Sustainability is embedded throughout the framework, with provisions for renewable energy systems, rainwater harvesting, and vertical greenery. These elements not only reduce the environmental footprint of urban development but also create a healthier and more aesthetically pleasing living environment. Elevated pathways and vertical hubs serve as platforms for integrating these sustainable features, reinforcing the city’s ecological resilience.

Culturally and socially, this design redefines the role of West Oakland’s main street as a dynamic urban artery. It preserves the historical and cultural significance of the area while introducing innovative functions that address contemporary urban challenges. The modular framework allows for the coexistence of modern development and historical preservation, ensuring that the community's heritage remains an integral part of its future.

By leveraging modularity, verticality, and community-driven development, this concept offers a scalable and adaptable solution for urban growth in West Oakland. It transcends traditional planning paradigms by empowering residents to shape their environments, fostering inclusivity, and promoting sustainable development. This vision transforms West Oakland’s main street into more than just an infrastructural element—it becomes a nexus of cultural, social, and spatial innovation, bridging the present and future of urban living.

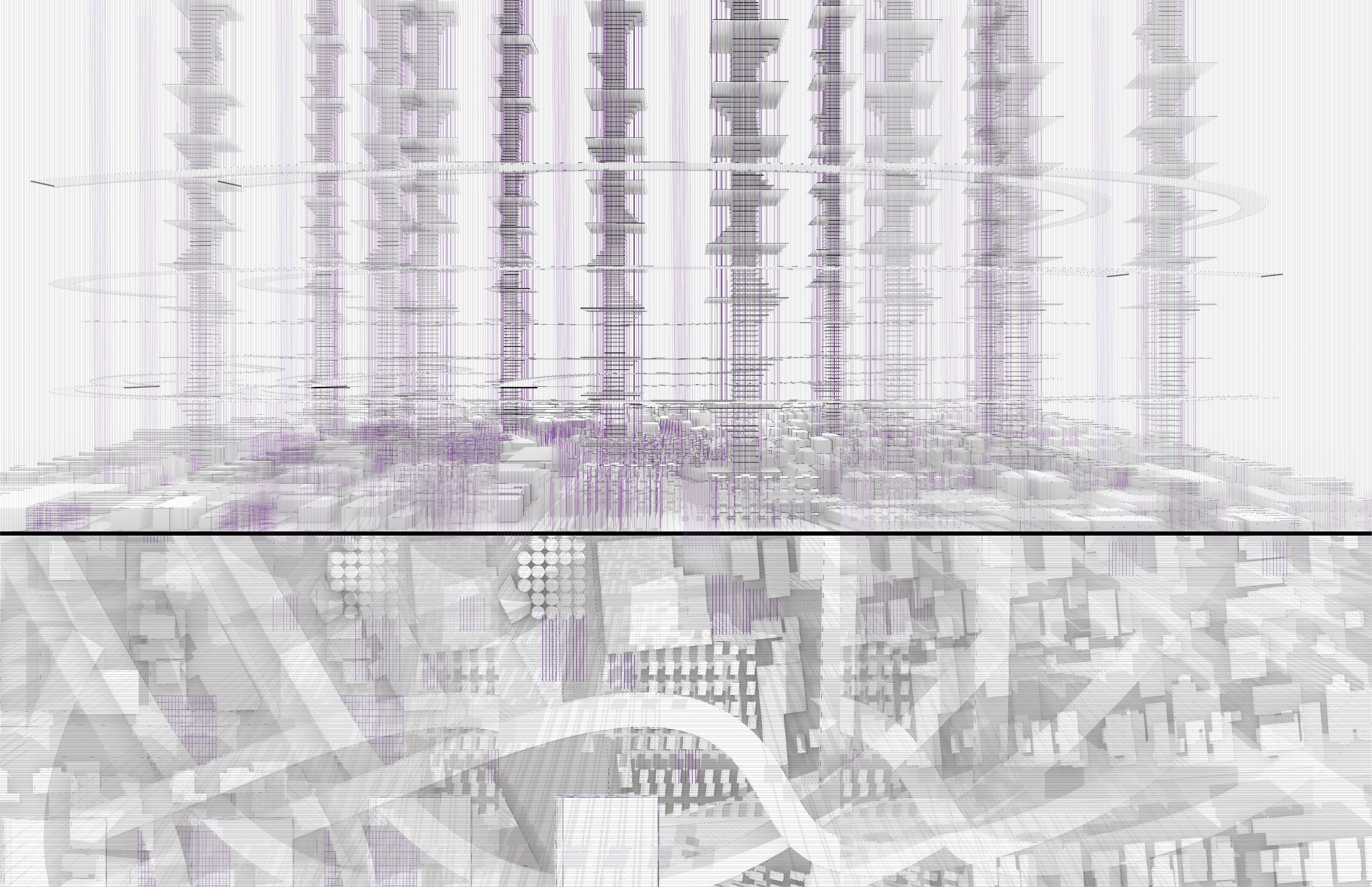

Conceptual Diagrams

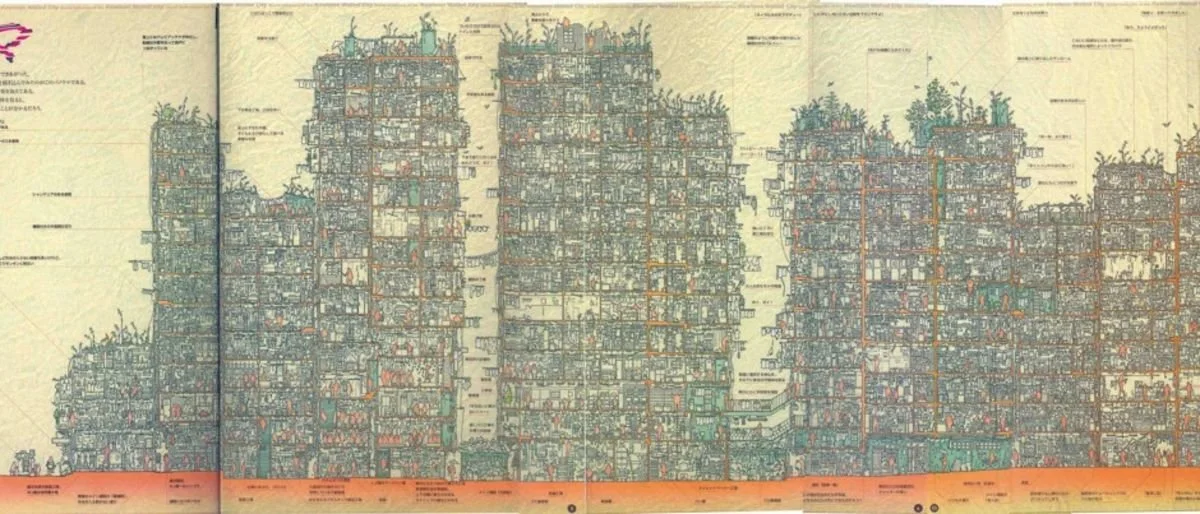

Kowloon Walled City_1989_Aerial

A team of researchers illustrated the insides of Hong Kong's hub of vice. Kowloon large illustrated

A team of researchers illustrated the insides of Hong Kong's hub of vice. Kowloon large illustrated

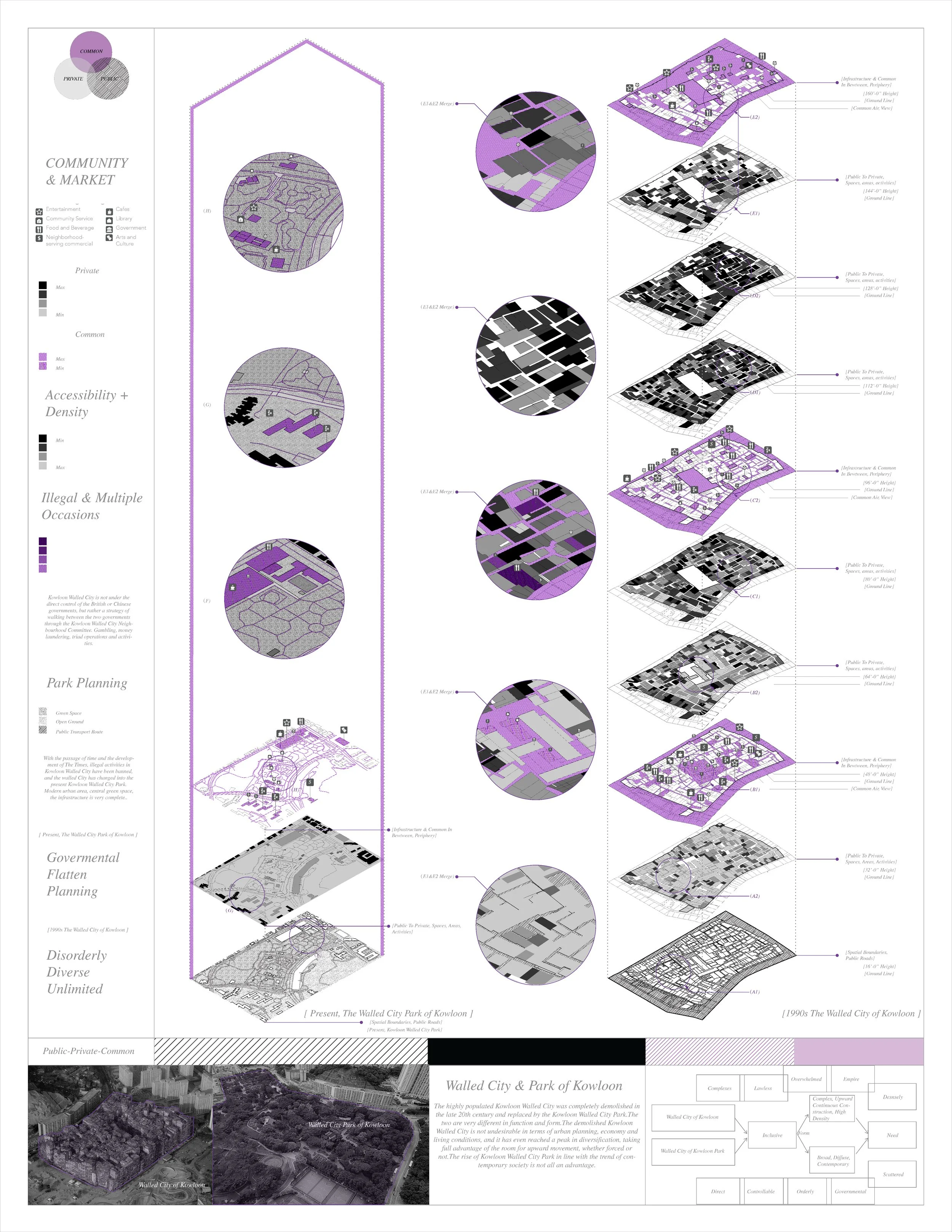

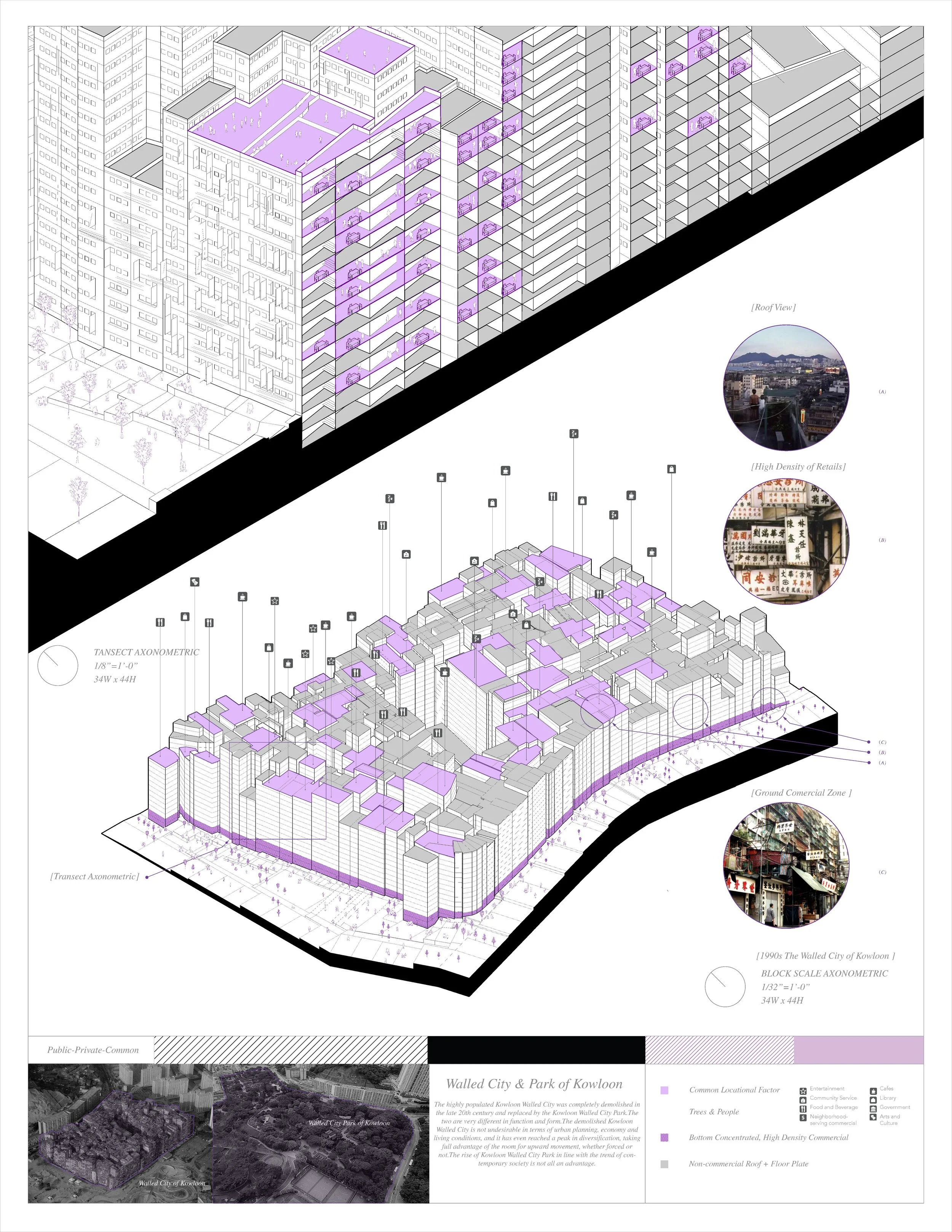

Analysis Diagram_ Kowloon Walled City

Analysis Diagram_ Kowloon Walled City

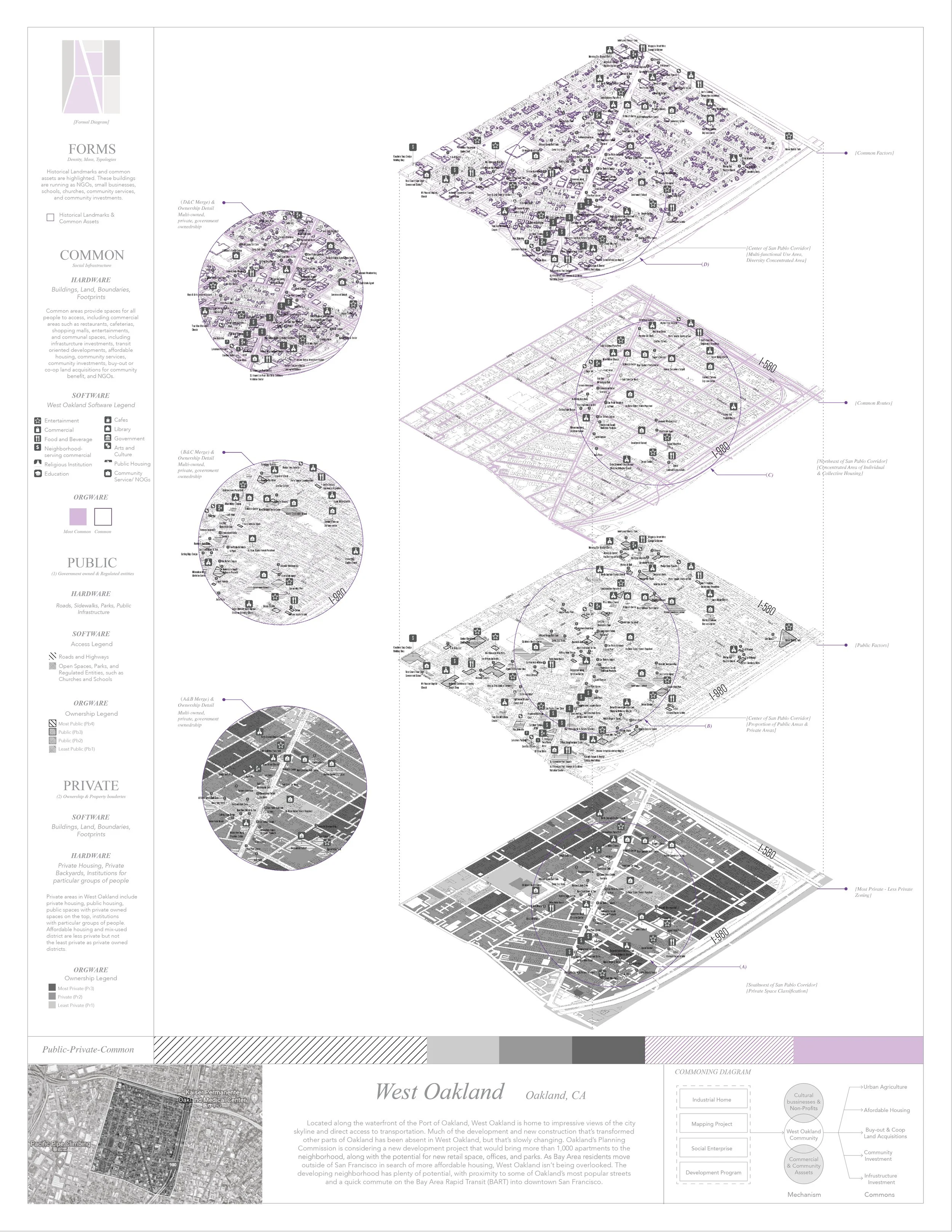

Analysis Diagram_ West Oakland

Analysis Diagram_ West Oakland